Gender and education gaps in presidential voting over the past several decades

How the parties flipped places

There’s going to continue to be a lot of talk about the gender gap and the education gap this election season, so I thought I’d level set on both – what the patterns look like recently, how they’ve changed over time, what counts as a big gap, and that sort of thing.

I combined the American National Election Studies from 1948 to 2020 with the General Social Survey from 1972 to 2022, both of which have asked respondents how they voted in the past couple of presidential elections, providing a pretty good baseline for estimates of gender and education effects across time.

The gender gap

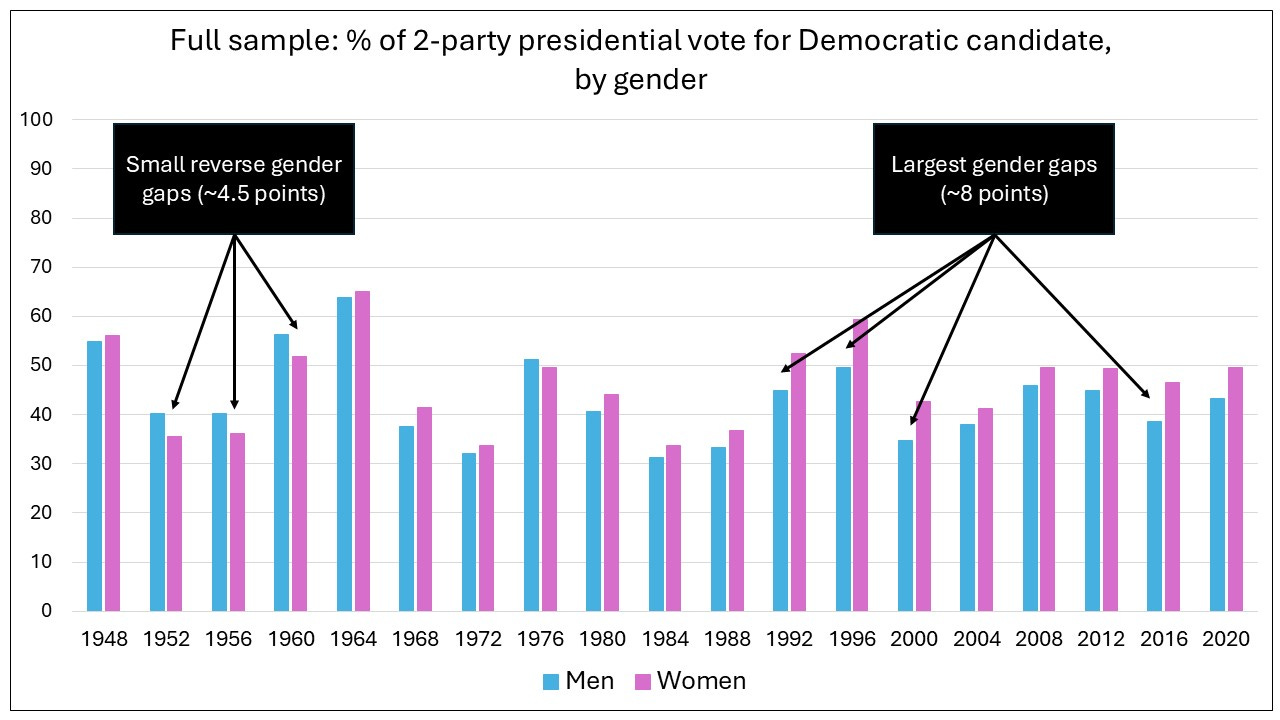

The graph below shows the gender gap going back to the 1948 election. You can see that the elections from 1952 to 1960 actually seem to have produced a small gap that is the reverse of our current gap – women apparently liked Ike a bit more than men did overall. The modern gender gap appears to have become persistent beginning in 1980 – Reagan’s first election – and was particularly wide in the Clinton elections (involving both Bill’s two and Hillary’s one). The widest gender gap we’ve had over this time period, according to this dataset, was in Bill’s second election in1996, with a gap of around 10 points.

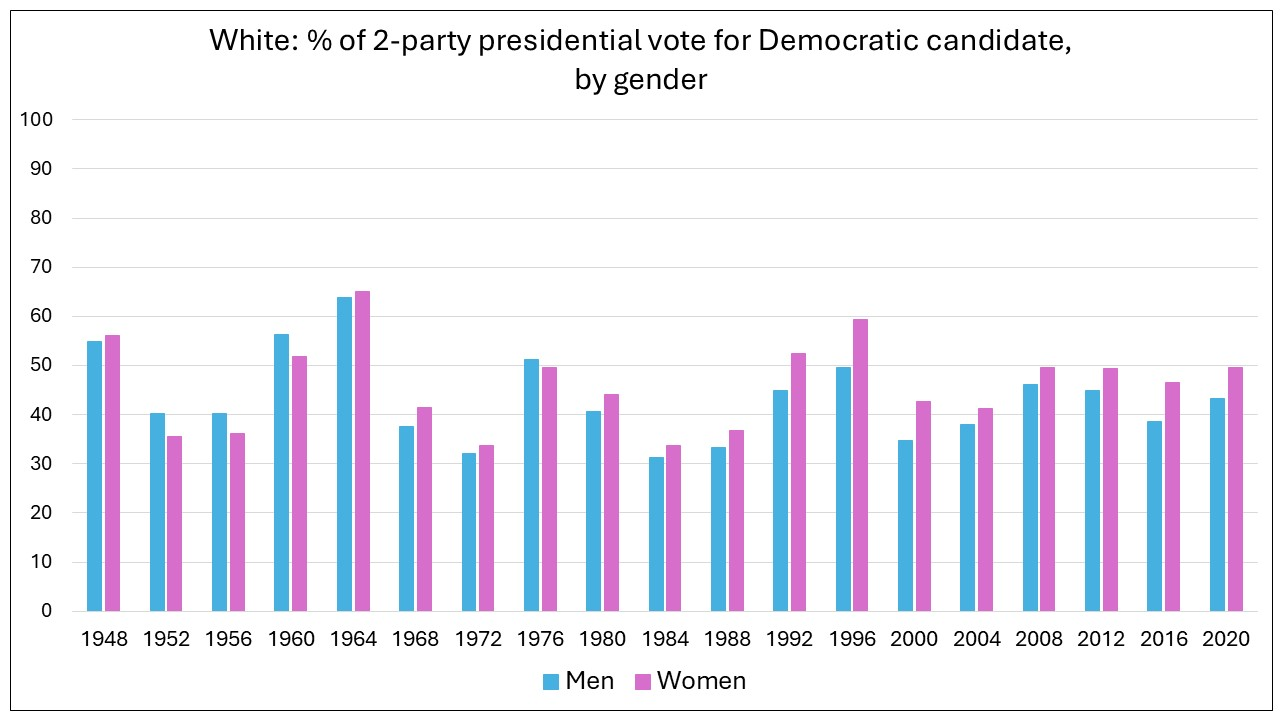

Now I’ll break it down by race. First is the gender gap between (non-Hispanic) White women and White men. It looks a lot like the full-sample chart, just with lower baseline support for Democrats overall.

Next we see the gender gap for Black Americans. I excluded 1948 to 1956 given that the sample sizes for Black voters was really very small.

The gender gap among Blacks has tended to be pretty small. Notice the recurring pattern in which support for Democrats shoots up very high at different points, and then generally creeps back down until the next rise. In most of these cases, especially recently, the fall away from Democratic votes was led by Black men. The current worries from Democrats about eroding support from Black men would have been essentially the same in the early 2000s as they are today. What we have yet to see is whether – and to what extent, and for whom – this election will be associated with a re-solidifying of Black support for Democrats.

Next, for completeness, I show the gender gap for the rest of the sample – mostly made up of Hispanics and Asians. Here, the sample sizes don’t really allow you to see anything before the late 1980s, and even then, numbers for the first few elections should be taken with a grain of salt. Here we generally see pretty big gender gaps in recent elections, though with a lot of variation.

The (simple) education gap

The modern education gap has primarily occurred among (non-Hispanic) White Americans, so I’ll keep my focus there. Just looking at the simple divide between those who have 4-year college degrees vs. those who do not, the differences are shown in the next chart.

As you can see above, the first 20 years of this dataset show more support for Republicans among college Whites than among non-college Whites, which is the reverse of our modern pattern. And these weren’t small gaps – in most of these early elections, the education gap exceeded 10 points. Then we roll through a series of small and inconsistent education gaps in the 1980s through the 2000s – until things shift a bit over the Obama elections but then move quite abruptly with Trump’s first contest in 2016. We see the college vs. non-college gap among Whites go from around 6 points from 2000 to 2012 to around 24 points in 2016 and 2020.

But that simple look at college vs. non-college actually obscures how the historical education flip between the parties happened. To see that, we need to look at a more-complex educational split that reveals what was going on in those middle years.

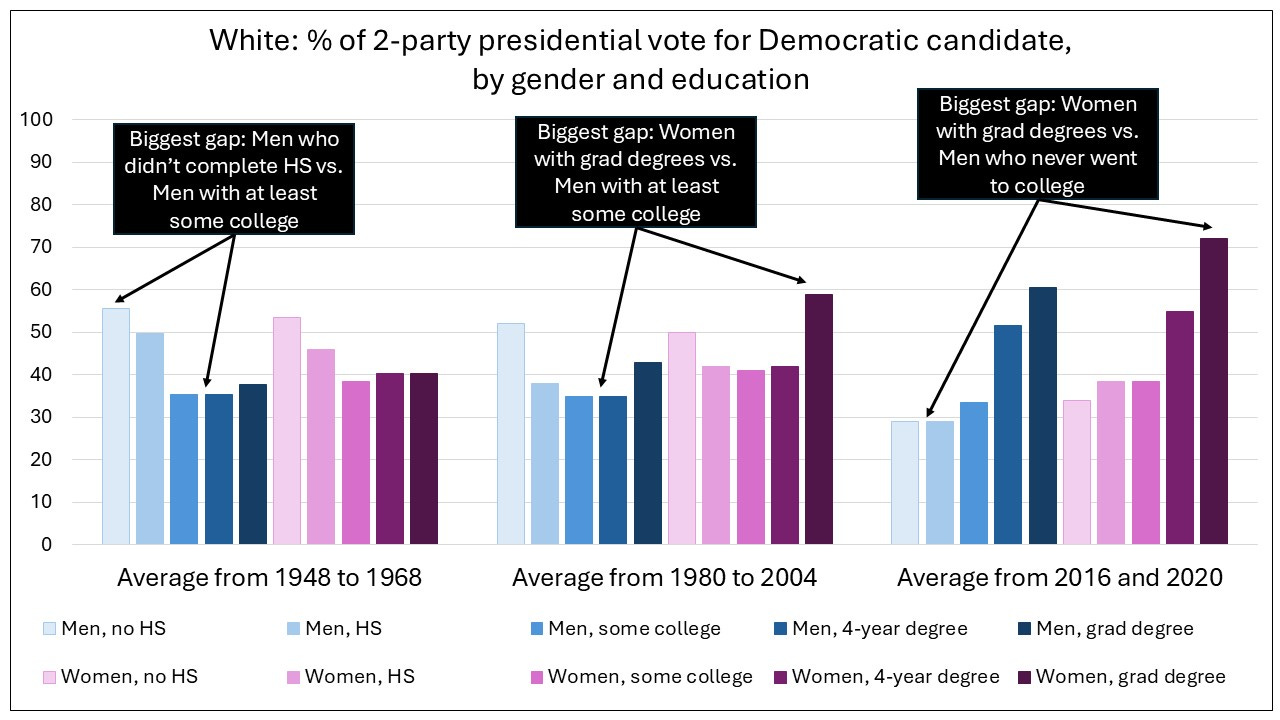

Combining a more-complex education split with gender

In the chart below, I’ve split out White Americans’ education into five categories: no high-school diploma/GED, high school complete but no college attendance, college attendance but no 4-year degree, 4-year degree but no graduate/advanced degree, and finally those with a graduate/advanced degree. I’ve also split things by gender. And to dial down the complexity, I averaged together voting across three sets of distinctive elections: 1948 to 1968, 1980 to 2004, and 2016 and 2020.

Now we’re cooking. Think about it in terms of the implied coalitions. In the 1948 to 1968 elections, on average, you were most likely to find Republicans among (1) Whites with at least some college (including those with degrees) and (2) White women who finished high school but didn’t attend college. Conversely, you were most likely to find Democrats among (1) Blacks and (2) Whites who didn’t finish high school. As for White men who finished high school but didn’t attend college, they were a nearly perfectly balanced swing demographic.

Moving to the 1980 to 2004 period, you can see that there is a distinctive education pattern over this period, but one that won’t show up in a simple college vs. non-college split. Instead, among White Americans, this period pitted the middle of the education distribution against the two ends, that is, against both those who didn’t finish high school and those who made it all the way to graduate/advanced degrees.

And you can also see that the gender difference is driven mostly by the higher end of the education ranks.

Again, think about it in terms of the implied coalitions. In the 1980 to 2004 elections, on average, you were most likely to find Republicans among (1) Whites with at least a high school diploma but not a graduate/advanced degree and (2) White men with graduate/advanced degrees. Conversely, you were most likely to find Democrats among (1) Blacks, (2) Hispanics/Asians, (3) White women with graduate/advanced degrees, and (4) White men who didn’t finish high school – this is, to say the least, a really heterogeneous political coalition. As for White women who didn’t finish high school, they were a nearly perfectly balanced swing demographic.

In the 2016 and 2020 numbers, we see Democratic support coming mostly from (1) Blacks, (2) Hispanic/Asian women, (3) White women with graduate/advanced degrees, (4) Hispanic/Asian men, (5) White men with graduate/advanced degrees, and (6) Whites with 4-year degrees but not grad degrees. On the Republican side, you’re now more likely to see support from Whites who don’t have 4-year degrees.

So it appears that this is how the parties flipped: In the middle of the 20th century, we had parties roughly sorted into an upper-middle-class party (Republicans) and a working-class party (Democrats). In the late 20th century, highly educated women joined the Democratic coalition, and highly educated men started moving in that direction as well. There was a small shock to that system in the Obama elections, where you see low-education Whites starting to drift to the right of high-education Whites. And then Trump’s nomination very rapidly accelerated that trend. The result is essentially a reversal of the mid-20th century parties, except not fully, given that Black Americans have remained Democrats and still have lower socioeconomic status on average.

What to look for this time

These analyses help to set the stage for the current election. What would a big gender gap look like? Well, the biggest in the past several decades have been in the 7 to 10 point range. If we see anything above 10, it’ll be a big deal.

Will the White college gap increase? It’s been around 24 points in the last two elections. Will the education gap show up distinctly in Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians? In past elections, you don’t see big partisan gaps by education with racial minorities, except in the universal way in which less-educated voters tend to be less engaged than more-educated voters.

How will the gender and education gaps relate to one another? Among Whites, the gender gap has primarily been driven by highly educated folks, where men have trailed women in moving towards Democrats over the past 40 years. How will these interact this time, given, e.g., a female candidate on the ballot as well as the centrality of the abortion issue following the overturning of Roe v. Wade?

I think there are plausible reasons to expect increases in both of these gaps this cycle, but, as the saying goes, prediction is hard, especially about the future.