The evolving presidential electorate

How demographics that should have favored Democrats from 2008 to 2020 were offset by within-group shifts

As the U.S. has become less White, less religious, and more educated, the growing groups have tended to be those that favor Democrats over Republicans. And yet the two parties have maintained a relatively stable split of the two-party presidential electorate, with Democrats outperforming Republicans by a few points in the popular vote while Electoral College outcomes have been on a razor’s edge and essentially a toss-up in the past few elections.

Given the sizable demographic shifts, the relative stability in presidential outcomes implies that there have been changes within demographic groups that are balancing things out. That is, there must have been shifts in two-party voting and/or turn-out patterns helping to move votes from Democrats to Republicans to offset the constant leftward push of demographics.

To make sense of these matters, I take a look here at data from the 2008 to 2023 Cooperative Election Studies (N ~ 586,000) – see the note at the end of this post for more detail. I split the full sample by race (White, Black, and Hispanic/Asian). I divided Blacks into older and younger generations. I divided Whites and Hispanics/Asians by religious identity, with Evangelicals on one side, explicit non-Christians on the other (i.e., self-described atheists, agnostics, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and Hindus – which for convenience I call “Heretics” – FYI, I’m a Heretic on this definition, so it’s meant to be usefully brief rather than conveying any political message), and those in the middle (including Mainstream Christians and also “none of the above” and “other” categories). Then I split most of the White subgroups by whether folks had 4-year college degrees or not, except for White Evangelicals, where education differences are trivial and instead a big split these days, similar to Blacks, is between older and younger generations. And I made a couple of further key splits in the biggest remaining subgroups.

Changes in the demographic make-up of the electorate

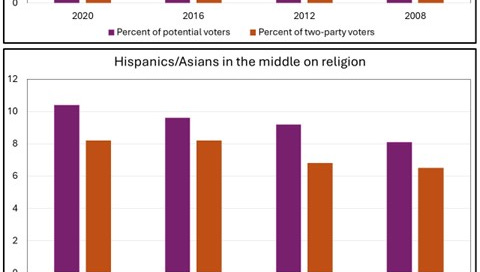

Let’s just dive into the charts below and you’ll figure it out. In the first panel below, you can see that Blacks who are Gen-Xers, Boomers, or older: (1) have been declining both as a percentage of the potential voting population and as a percentage of actual two-party voters (which is of course going to be the case given that a group defined by year of birth that has already fully passed voting age must necessarily diminish over time, unless you’ve got enormous amounts of immigration within that group); and (2) consistently punch above their weight – that is, their percentage of actual two-party voters is higher than their percentage of potential voters. In other words, they’ve had high turn-out rates relative to other groups. In contrast, Millennial and Gen Z Blacks have generally had low turnout rates, especially in the last two elections. Hispanics and Asians also tend to punch below their weight. In general, you can see that Hispanics/Asians are growing as a percentage of both the population of potential voters and the two-party electorate, while Blacks are growing in population but not as much as a percent of actual voters, given their reduced turnout post-Obama.

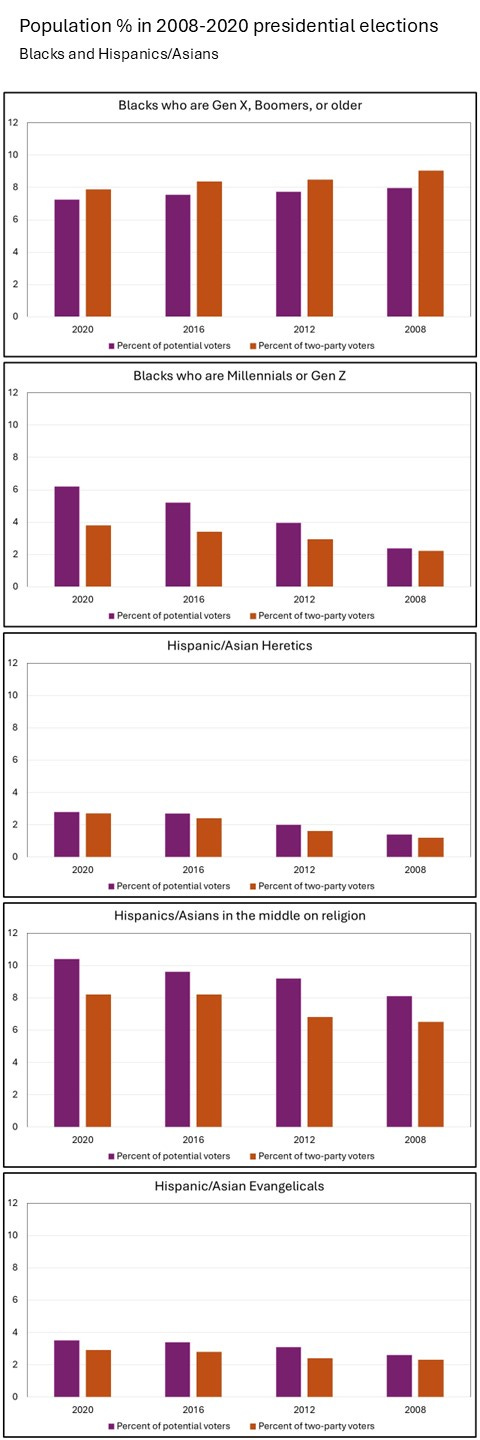

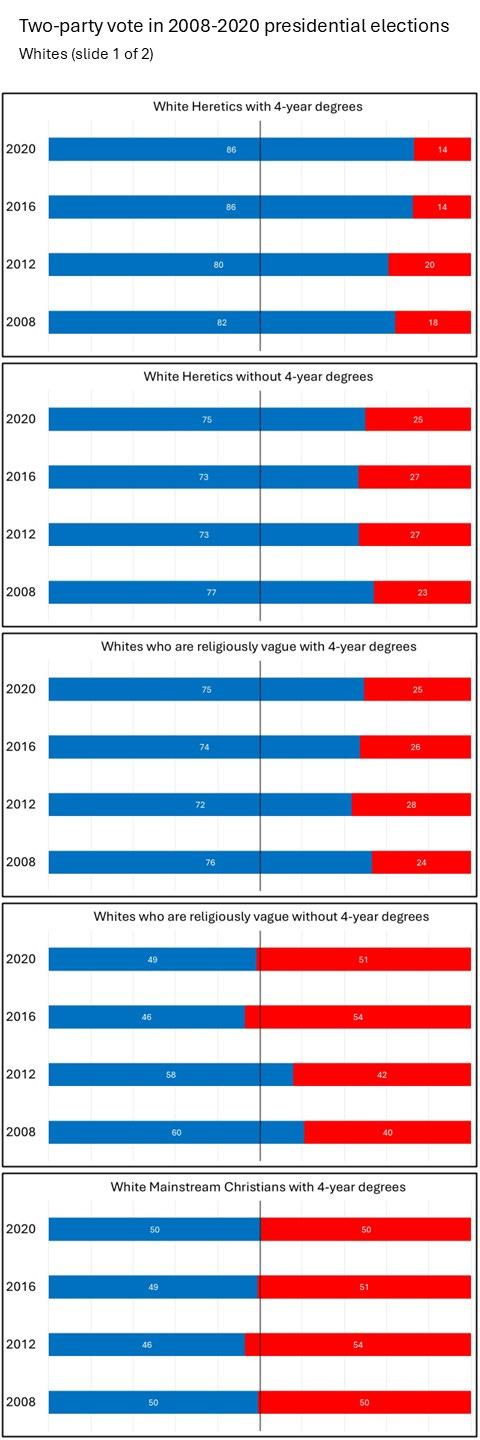

Generally speaking, people are more likely to vote these days to the extent they are more highly educated, older, richer, are more religiously involved, have lived in their communities longer, and so on. For example, in the next series of charts, you can see that the college-educated groups generally have been higher percentages of actual voters than they are of potential voters. You can also see the biggest underperforming group in these charts: Whites without 4-year degrees who say “nothing in particular” or “other” when asked about their religion. One group you see having an increasing impact on elections is White Heretics with 4-year degrees (congrats to my people!). This group has generally been growing as a percent of potential voters and increasing their turn-out rates, resulting in a move from being less than 5% of two-party voters in 2008 to around 8% in 2020.

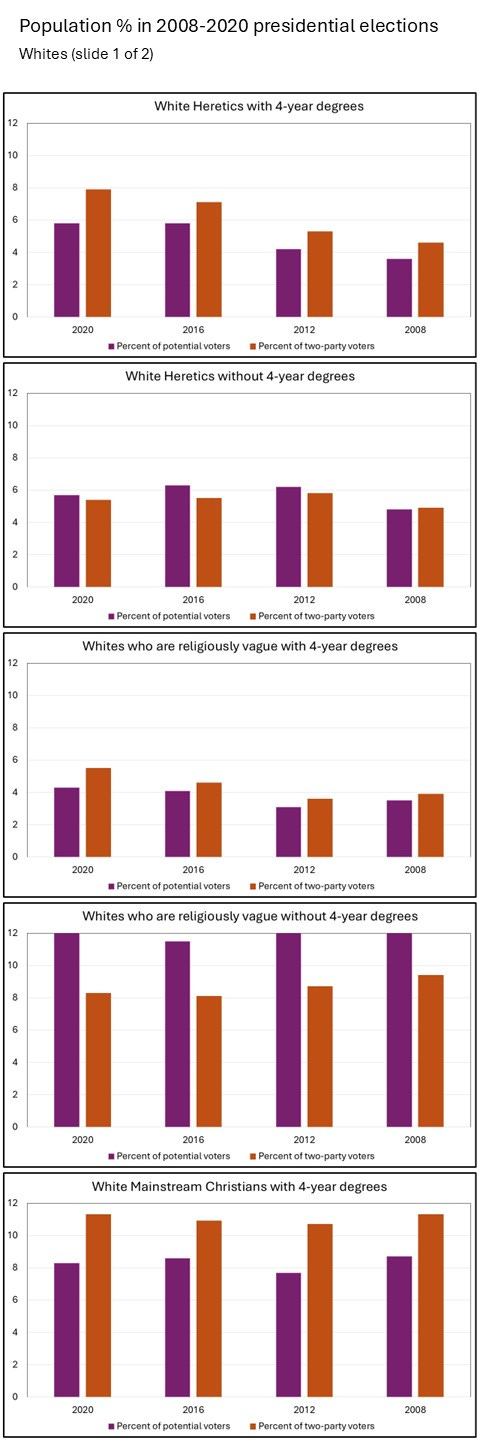

So we’ve seen the key growing demographic groups – racial minorities along with educated Heretics. The next series of charts show the central declining groups, primarily less-educated White Christians. You also see examples of higher turnout among older and more religiously engaged voters.

What were the partisan shifts within the various demographic groups?

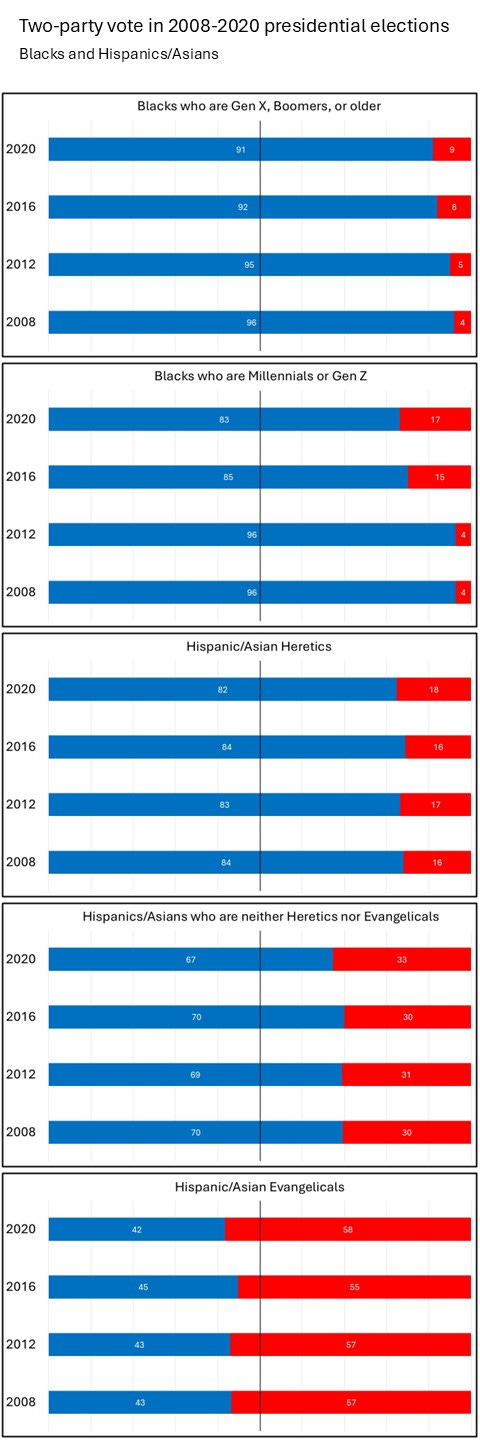

In terms of two-party presidential voting, a number of demographic subgroups have shifted to the right over the past four elections. One key shift shown below has come from Blacks, who, in the Obama elections in 2008 and 2012, had moved almost entirely to Democrats, with Obama getting around 96% of the two-party vote, and have since become less monolithic. This has been especially true with younger Blacks, who gave Trump around 17% of their two-party votes in 2020. In addition, Hispanics and Asians shifted ever-so-slightly to the right from 2008 to 2020, just perceptible in the series of graphs below.

Another group that has shifted significantly the right, shown below, are Whites who chose vague survey options relating to religion, including “nothing in particular” and “other,” and who do not have 4-year college degrees. They went from 60% for Obama in 2008 to less than 50% for Biden in 2020. Other groups of non-Christian (or not-explicitly-Christian) Whites, on the other hand, don’t appear to have had similar rightward movement, nor do White Mainstream Christians with 4-year degrees, who have remained pretty close to 50-50 in the past four presidential cycles.

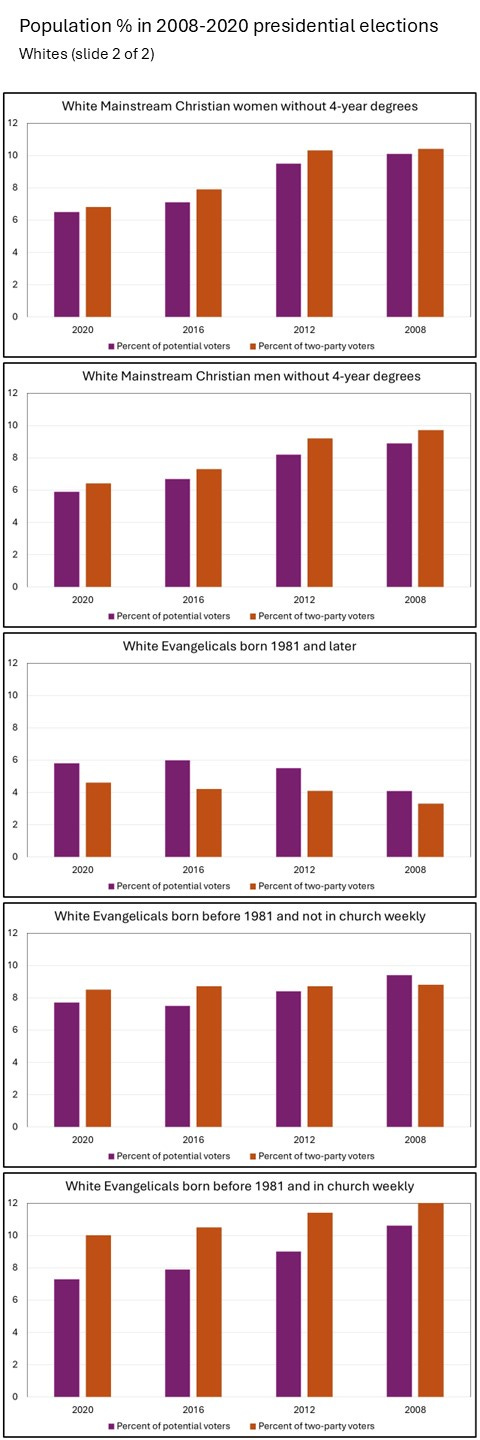

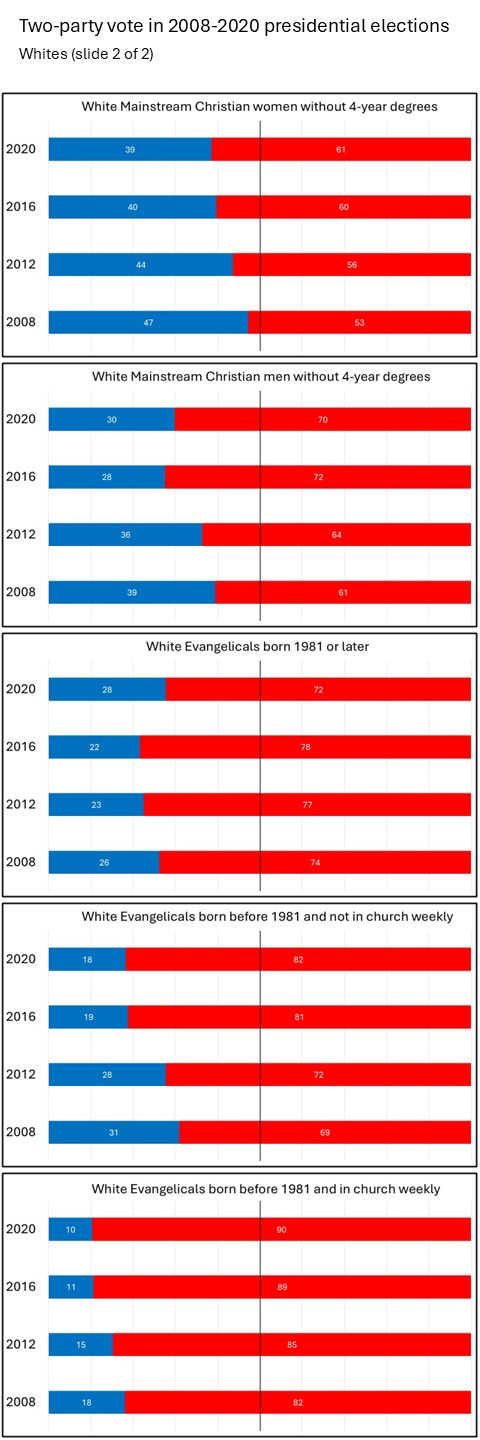

Finally, the third series of charts below shows groups that had big Republican shifts in two-party presidential voting. White Mainstream Christian women without 4-year degrees went from 53% Republican in 2008 to 61% in 2020. White Mainstream Christian men without 4-year degrees went from 61% Republican in 2008 to 70% in 2020. Older Whites who identify as Evangelical but who don’t go to church weekly went from 69% Republican in 2008 to 82% in 2020, while their weekly churchgoing neighbors went from 82% in 2008 to 90% in 2020. The only group here that didn’t shift further towards Republicans overall is younger White Evangelicals, who seem to have reversed their rightward trend in 2020.

Overall, it looks like we’re seeing big shifts in two-party presidential voting within most groups of less-educated and/or more traditionally religious Whites, and also within Blacks. The White shifts look to me like issue-driven coalitional shifts – caused primarily by Trump’s emphasis on facilitating traditional group-based discrimination at the expense of both affirmative and meritocratic allocation regimes, something not seen with such clarity in presidential politics during most of our lifetimes. The Black shift is, to my mind, more of a post-Obama normalization than a more typical issue-led coalitional shift. It’s just not sustainable to have such a large and diverse demographic group preferring one party by 20+ to 1 margins in a two-party system over multiple elections.

Putting it together

The main story here is that the core groups that are declining the most in population – Whites who are less educated and more traditionally religious – are also the core groups shifting further towards Republicans in the two-party presidential vote. Then, within core Democratic groups, we see both a decline from the overwhelming Black support during the Obama elections, as well as a significant rise in the impact of White Heretics with college degrees.

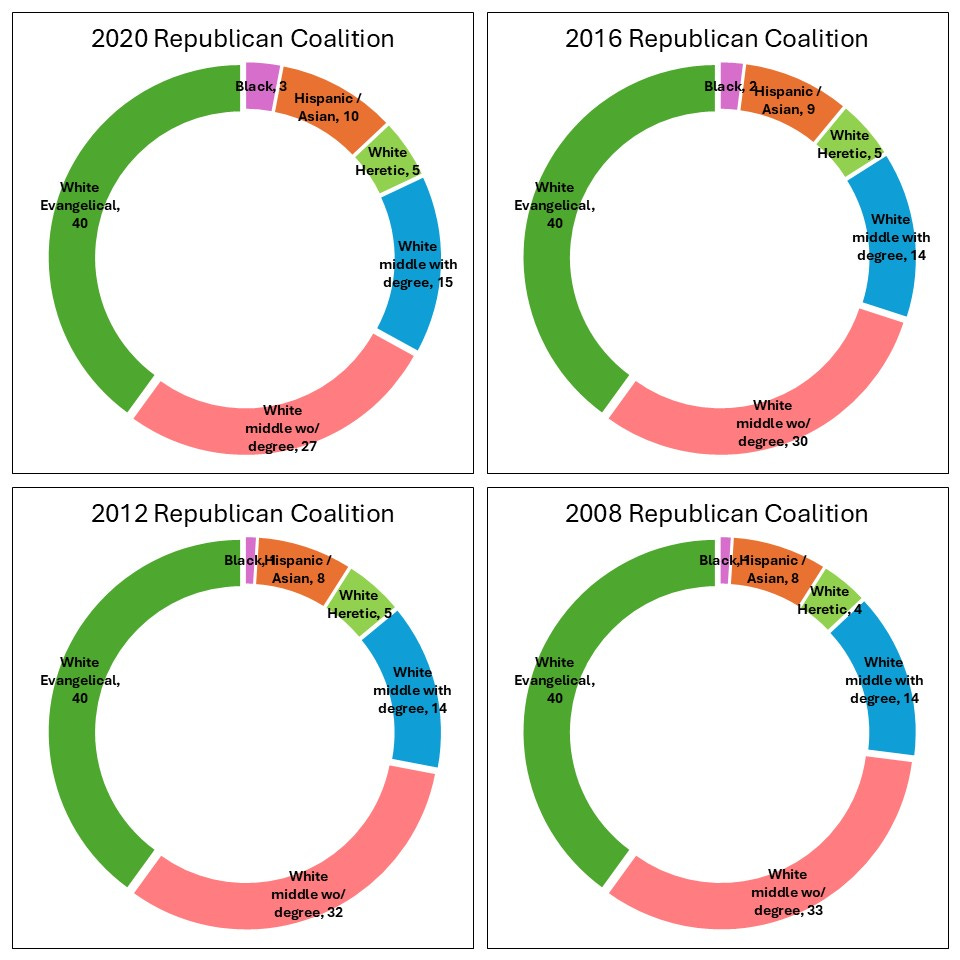

While the past few presidential elections have been pretty stable in terms of outcomes – small advantage for Democrats in the popular vote combined with very tight Electoral College contests – in fact this stability involves substantial (if counter-balancing) shifts underneath. You can see it by looking at changes in the demographic composition of the two parties’ coalitions.

As shown below, White Heretics were 14% of the Democratic coalition in 2008 but then 21% in 2020 and Hispanics/Asians rose from 12% to 17% -- together rising from 26% of Democratic voters in 2008 to 38% in 2020. On the other side of this coin, White Evangelicals dropped from 11% to 7% of the Democratic coalition and Whites in between Heretics and Evangelicals who don’t have 4-year degrees dropped from 27% to 16% -- together falling from 38% of Democratic voters in 2008 to 23% in 2020.

The Republican coalition, perhaps surprisingly, became somewhat more racially diverse since 2008, when Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians made up only around 9% of their presidential voters. In 2020, it was around 13%. The party’s percentage of White Evangelicals has remained remarkably stable at around 40% -- reflecting a near-perfect offset of population decline vs. increased voting margins. In the case of Whites in between Heretics and Evangelicals who don’t have college degrees, however, the increased Republican voting percentages have not kept pace with population decline, leading to this group forming a smaller percentage of Republican voters in 2020 (27%) than in 2008 (33%).

In sum, from 2008 to 2020, we saw:

Decline in population percentage of Whites who are less-educated and/or more traditionally religious, combined with increasing two-party margins for Republicans from these groups – with the end result that these folks primarily declined as a percentage of the Democratic coalition.

Population and turnout growth (and a small leftward partisan shift) among college-educated White Heretics, leading to a substantial rise in their percentage of the Democratic coalition.

Population and turnout growth (and a small rightward partisan shift) among Hispanics and Asians, expanding their percentage of both parties’ coalitions, with the bigger benefit going to Democrats.

A rightward shift among Blacks (and especially younger Blacks), leading to a small increase in their (previously super-tiny) share of Republican votes.

None of this tells you what’s going to happen this year. Mostly it’s just a reminder that electorates are constantly in flux and that this stuff is super complicated.

More to come!

Note on data: I started with the cumulative 2006 to 2023 Cooperative Election Studies. I discarded 2006 and 2007 because they didn’t measure some key demographics until 2008 (particularly on religion). I limited analysis to citizens. I looked for big-deal demographic differentiators among a number of variables – race, region, age/generation, gender, religion, church attendance, education, work status, income, home ownership, union membership, military service (family level), and marital status – and split up the sample accordingly. I then calculated survey outcomes for each demographic subgroup for the 2008, 2012, 2016, and 2020 presidential elections, recording, e.g., weighted number of Gen X and older Blacks who reported voting for Obama in 2008, voting for McCain in 2008, or not voting (or voting third party) in 2008. Then for each voting group (Dem Voters, Rep Voters, and Neither) across all demographic subgroups, I resized each voting group in total in accordance with (1) actual national popular vote numbers from that election and (2) voter turnout estimates from The American Presidency Project – the primary objective here was to compensate for the relative scarcity of non-voters in the CES. So, basically, the total relative size of the Dem vs. Rep vs. Neither options were set by external numbers, and then I assumed the CES’s percentage for each demographic subgroup within each of those three pools (using CES’s weighting).