The two main sources of individual differences in religious service attendance

One is parental attendance, but there’s another that matters at least as much.

The U.S., like many places, is becoming increasingly non-religious. These days, most folks hardly ever attend religious services – the median American adult attends about once a year. Nonetheless, there remains a pretty sizable chunk of Americans who are more-or-less regular communal worshippers – probably around a quarter of adults attend services at least a couple of times a month.

What are the big determinants of whether people end up being heavily involved with religious groups or not? That is, what are the primary drivers of individual differences in frequency of religious service attendance?

The best-known driver is familial inheritance. Some people grew up with high-attendance parents and others with low-attendance parents, and those who grew up with it are more likely to themselves attend as adults.

By itself, familial inheritance isn’t a particularly satisfying account of these individual differences. As it turns out, the relationship between frequency of parental service attendance and later adult service attendance just isn’t very large. It’s undoubtedly a real and interesting relationship, but just not in the size range where you’d plausibly think you’ve reached a good resting place for a serious investigation of these individual differences.

Take a look, for instance, at the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97), which started studying a big group of early Millennial teenagers in 1997 and has been repeatedly surveying them ever since. In that dataset, the correlation between how often their parents reported attending services in 1997 and how often the Millennial offspring were themselves attending services as adults is around .3. Compare this with the NLSY97 correlations between parental income in 1997 and offspring income in their mid-30s, or between parental education level and offspring education level – both of which are over .4.

Moreover, citing familial influence tells you nothing about why religious attendance has been declining over time. People who regularly attend religious services typically have more children than people who don’t attend. So, on average, most children grow up in above-average-attending households. Without considering more, a pure familial inheritance view would predict increasing attendance over generations, not decreasing attendance.

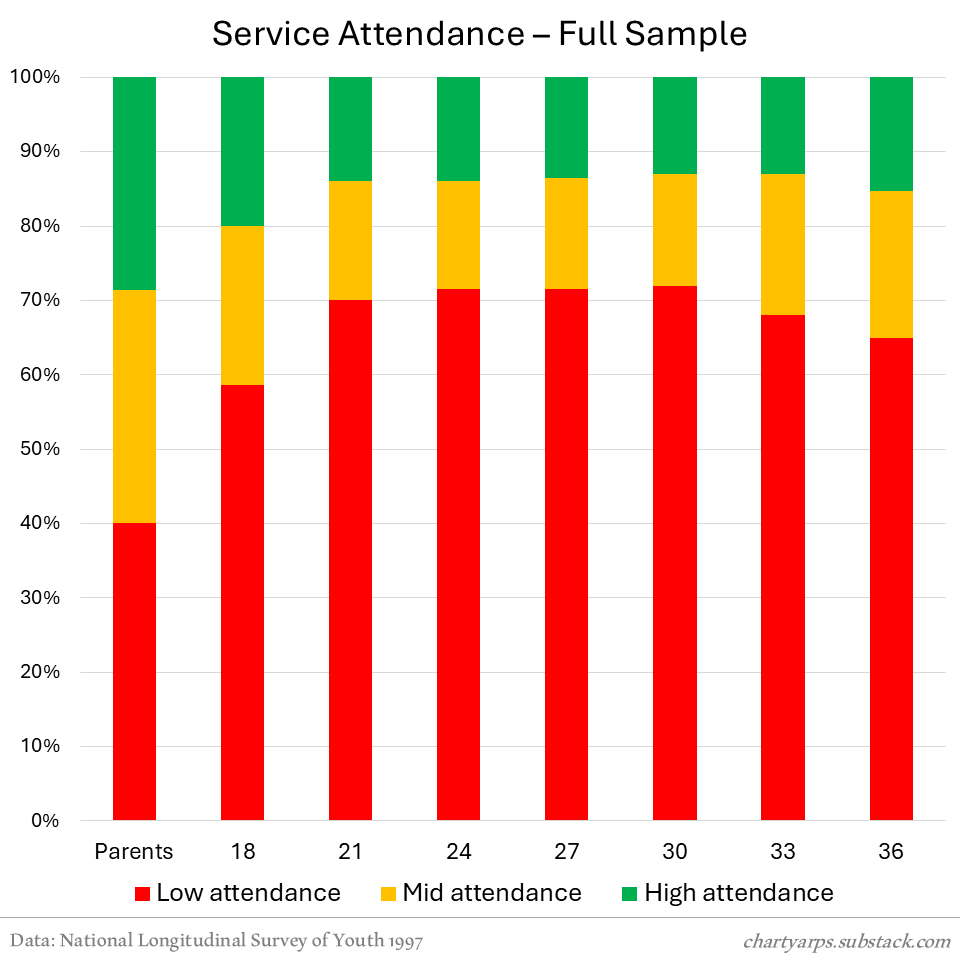

It’s been true for several decades at least that most Americans raised in regularly attending households are themselves not attending regularly by their mid-20s. Below is a chart based on NLSY97 data, showing parental attendance in 1997 followed by Millennial offspring attendance at ages 18 to 36. There, you can see that almost 29% of parents reported in 1997 (when their early-Millennial kids were in their mid-teens) what I’m calling “high attendance” rates – which I’ve defined to include those attending around once a week or more. In their 20s, in contrast, only around 14% of the kids have similarly high attendance rates.

On the flip side of that, around 40% of NLSY97 parents had what I’m calling “low attendance” rates, which I’ve defined as those going to services less than around once a month. By the time the sample offspring were in their mid-20s, the bulk of the sample – around 70% – had these low attendance rates.

So, something happens as we go through our teens and early 20s that not only directionally pushes down religious attendance rates, but also substantially loosens the relationship between parental religiosity and offspring religiosity. In addition to parental inheritance, this something is the other Pretty Big Deal in understanding individual differences in religious service attendance.

Rumspringa and the Call of Going Wild

The Amish in the U.S. are locally organized religious groups who often live in rural communities and, to varying degrees both within and between different groups, typically stay largely separate from non-Amish society, follow pretty strict codes of conduct, and forego many modern technologies. The 2002 documentary, Devil’s Playground, focuses on the experiences of Amish young people in Indiana who were in the midst of what is called Rumspringa, which means “running around” in the Amish language. While not universal or identical among Amish groups, Rumspringa relates to a period in their teens and early 20s when Amish kids have relaxed restrictions to some degree before either committing fully to an Amish lifestyle or else leaving the group entirely.

Devil’s Playground shows a particularly striking example of Rumspringa in which, starting in their mid-teens, the Amish kids are given surprisingly wide latitude that, for some, might involve mixing with non-Amish, driving automobiles (the Amish typically use horse-drawn carriages), partying, enjoying alcohol and recreational drugs, hooking up, shacking up, and so on. These kids were raised without television or other popular media, had no experience with parental models or even significant peer pressure that might push them to become promiscuous partiers, and yet significant numbers in their late-teens and early 20s were living it up in ways that are just very familiar to those of us who grew up in secular culture.

There are, of course, a range of individual differences for Amish young people in their responses to Rumspringa. Some remain dry, some dip their toes in the pool but don’t dive in, some take a lap and then get out and dry off. Most often, Rumspringa is concluded by the Amish young person deciding to marrying another Amish young person and fully joining the community.

But some find that a faster life suits them – so much so that they’re willing to separate themselves permanently from the communities they grew up in and follow a different path.

Rumspringa presents an extreme example of something more generally true of American religious life. These days in developed countries, being involved with a religious group is very strongly related to a range of lifestyle features forming a continuum anchored by what I have called “Freewheelers” on one end and “Ring-Bearers” on the opposite end.

The Freewheeler pattern involves lives with more partying (including alcohol and recreational drugs), more casual sex, more partners, fewer and shorter marriages, and having fewer kids. Think Sex and the City or Girls or some more recent analog.

The Ring-Bearer pattern on the opposite end involves little partying or casual sex, stable marriages, and more children. A prototypical Ring-Bearer would abstain from alcohol and recreational drugs, remain a virgin into their late teens or early 20s when married, be faithful and stay married, and have a bunch of kids – kind of an idealized version of what you might think of as the 1950s pattern that the free-loving 1960s rebelled against, or as the religious conservative gold-standard. Or as what the Amish are doing.

The Amish follow a pretty narrow Ring-Bearer path. The type of Rumspringa depicted in Devil’s Playground is, centrally, an opportunity for these kids to flirt with Freewheeling. If they decide a Freewheeling lifestyle is what they want long-term, then they leave their Amish homeland. If in the end they choose the Ring-Bearer path, then they willingly subject themselves to Amish restrictions.

A similar process drives the decline more generally in religious participation that we saw in the chart earlier based on NLSY97 data. The decline happens in their teens and early 20s and is substantially correlated with Freewheeler vs. Ring-Bearer lifestyle differences. Basically, the teenage decline in religiosity in the general population doesn’t happen to everyone who was raised religious – it is concentrated among those who follow a Freewheeler path. Those raised in high-attendance homes are far less likely to abandon high-attendance when they have Ring-Bearer patterns.

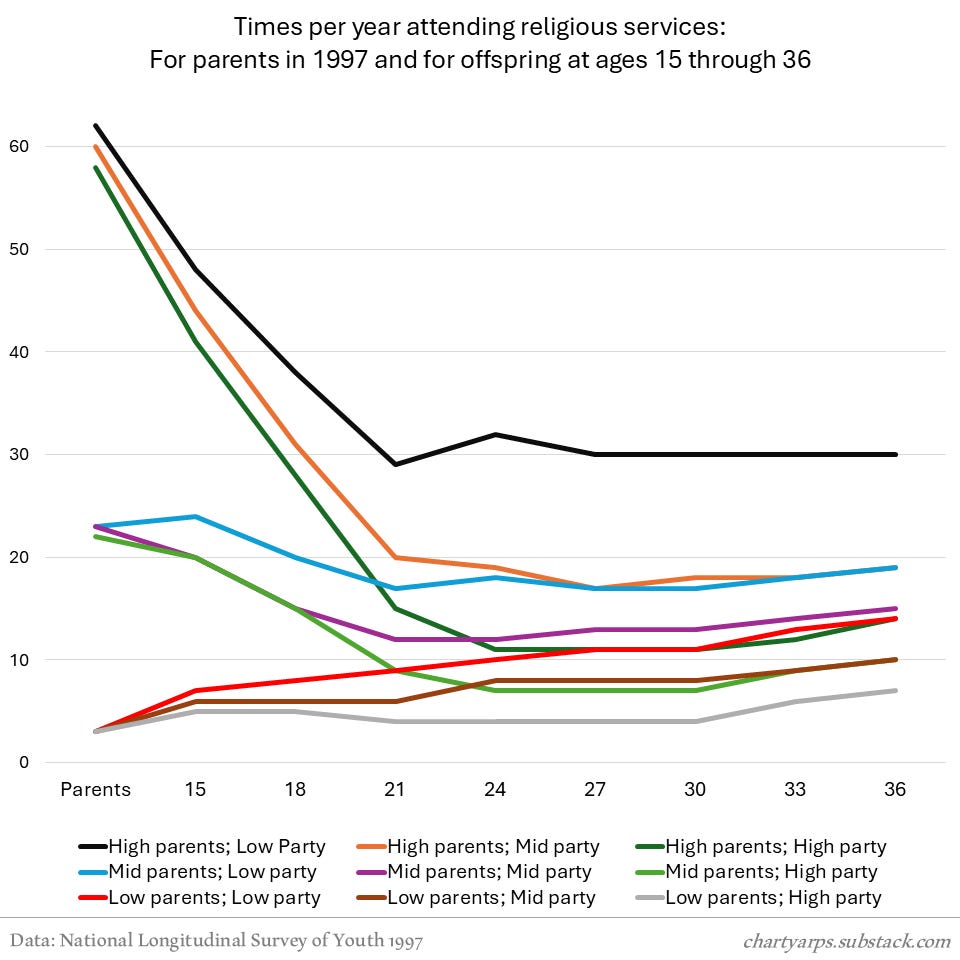

Here's a simple look at the pattern nationally. I split out the NYSY97 sample by (1) whether the parents were high attendance (i.e., weekly or more), low attendance (less than monthly), or mid attendance (in between high and low), and (2) whether the Millennial offspring had high rates of drinking and using marijuana in their early 20s (high party), low rates (low party), or something in between (mid party). So that’s nine groups: High parental attendance with a low level of partying in early 20s; high parental attendance with a mid level of partying in early 20s; and so on.

The graph shows the nine groups’ average times per year attending religious services. You can see that the only group ending up with pretty high average attendance rates as adults were those who both had high attendance parents and little partying in their early 20s.

But doesn’t their parents’ religiosity relate to the offspring’s likelihood of going wild? Yes, but it’s not a strong relationship. In the NLSY97 data, the correlation between frequency of parental attendance and the kids’ rates of using alcohol and marijuana in their early 20s is -.125. It’s clear that there’s a lot more that goes into determining whether young adults hear and heed the call of going wild or not, something suggested by the mere existence of the Amish raves depicted in Devil’s Playground.

The Elephant in the Pews

Lots of things correlate with religiosity. Black Americans are more likely to attend religious services than other groups. Women are more likely to attend than men. People with agreeable and conscientious personalities are more likely to attend. Religiosity has interesting relationships with age and cohort, aspects of cooperation, social mistrust, certain of the Schwartz values items, and so on, and so on.

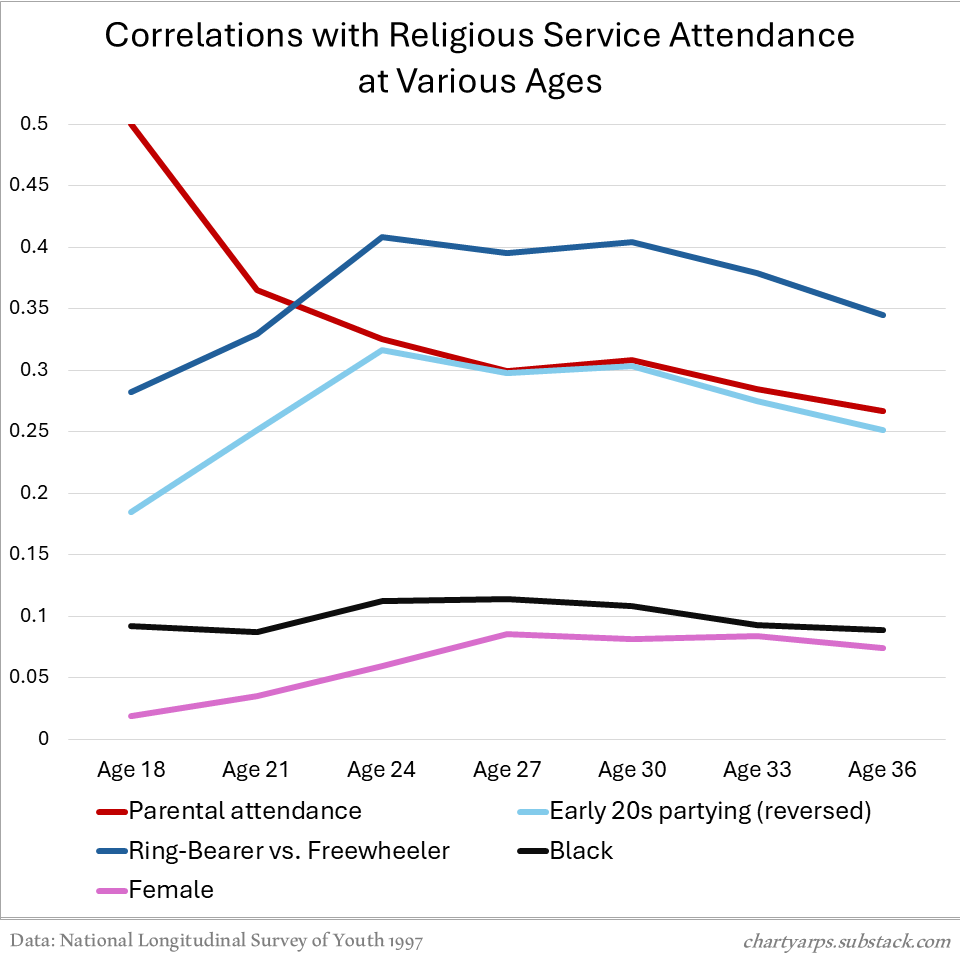

But size matters. In large samples or meta-analyses, all of these relationships result in correlations that are typically in the .1 to .2 range. In contrast, items relating to Ring-Bearer vs. Freewheeler lifestyles can hit .3 or more without breaking much of a sweat – keep in mind parental attendance rates are also in that .3 range when predicting offspring adult attendance.

Here’s a look at some correlations from the NLSY97 data. So, check out the red line – this shows the correlations between parental attendance rates and offspring attendance rates at ages 18 to 36. It starts off huge, but as folks leave their parental homes, it declines quickly in predictive force. The blue lines are lifestyle measures. The light blue line shows correlations between religious attendance rates and a simple measure of frequency of alcohol and marijuana usage at ages 21 and 24 (I reversed the measure to make it a positive correlation, so this is telling you that less partying is associated with more churchgoing). By age 24, this simple measure is as big of a correlate – around .3 – as parental attendance rates. The dark blue line is a better Ring-Bearer vs. Freewheeler scale I put together that adds points not just for abstaining from alcohol and pot, but also remaining sexually abstinent, getting and staying married, and having more children (though not having them when super young). Here the correlations with service attendance are around .4 from mid-late 20s to early 30s.

The absolute biggest correlations with religiosity known to mankind these days are moralizations about Ring-Bearer vs. Freewheeler lifestyles. Religious worshippers aren’t just people who tend to live Ring-Bearer lifestyles – they’re people who typically seek to defend Ring-Bearer lifestyles in part by building communities that support sociosexual restrictiveness, marital stability, and large families, and in part by trying to increase the social costs of Freewheeler lifestyles.

You can see in large studies how sexual and reproductive variables absolutely dominate more widely discussed correlates of religiosity. It’s just not a close call – a well-constructed Ring-Bearer vs. Freewheeler measure will typically practically fully mediate things like Big 5 personality, age/cohort, gender, cooperative morals, and social mistrust.

In the end, there are two big-time predictors of religious service attendance. One is parental attendance. The other is the commonly unrecognized elephant in the pews: sexual and reproductive lifestyles.

Part of the reason some researchers don’t think about these lifestyle correlates as big deals in explaining individual differences in religiosity is that they think of lifestyles as exclusively effects and not causes of religiosity. To a degree, of course, some lifestyle features are definitely affected by religiosity.

But there are strong reasons to think that lifestyle preferences are also affecting decisions to stay, leave, or join religious groups. One is that it helps explain the big drop in attendance for those raised religious, which happens to happen in the same years in which kids are starting to explore sociosexual space. And it just so happens that their decisions to cut back on attendance rates or not are strongly correlated specifically with whether they start engaging in Freewheeler lifestyle patterns. In sorting this out, you could stick to a religion-as-cause story and say something like: The drop in service attendance is caused by some unknown force, but it’s that drop in religiosity that then causes formerly high-attending kids to start partying and hooking up. Or you could adopt a religion-as-both-cause-and-effect story that probably makes more sense: Some kids are raised going to religious services but then later, as they enter sexual maturity, for reasons unrelated to (and despite) their prior religiosity, some of them engage in promiscuous partying – and when that lifestyle shift occurs, they tend to decide that embedding themselves within religious groups doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Other reasons to think that lifestyle preferences are among the causes (and not just effects) of people’s religious patterns involve the correlation and mediation patterns, and also just taking evolutionary biology seriously. But I’ll leave those discussions for another day.

To wrap this one up, in summary: In the contemporary U.S. and places like it, there are fundamental individual differences in the extent to which folks affiliate with religious groups. This is partially explained by differences in parental patterns, but we can also account for a good portion of the holes left over by parental influences by recognizing that the relatively large lifestyle correlates of religiosity result in substantial part from people adjusting religious patterns in response to changes in their own lifestyle preferences or features.